Building Data Pipelines Like Assembly Lines

19 min read |

This is a story about a small team of data engineers at Astronomer who decided to stop hand-stitching every pipeline like artisanal Brooklyn cobblers and started building them like Ford Model Ts – with interchangeable parts, quality control, and the confidence that comes from doing the same reliable thing over and over again.

Not by working harder or being smarter, but by taking an industry pattern, write-audit-publish, and enforcing it ruthlessly with Airflow Task Groups and a DAG factory.

We built a declarative framework for defining Airflow pipelines where tasks are self-documenting and metadata-driven. This let us focus on business logic – the SQL queries, Python functions, and data validations that actually matter – while a set of reusable Task Groups handles all the orchestration plumbing.

Now we spend our time writing code that answers business questions, not writing boilerplate that wires up operators. And we deliver that code at ludicrous speed.

The Problem: Imperative Pipelines Don’t Scale

It’s a run-of-the-mill Tuesday morning and Marketing requests campaign attribution data. You unremarkably spend 3 days building a pipeline: hit the API, write to some cloud storage, load to your data warehouse, transform, publish. End of the week, all done, bring on the weekend.

Two weeks later, Sales requests opportunity tracking. You spend 2 more days building essentially the same pipeline but just different enough that you can’t reuse the code.

We were solving the same fundamental challenge over and over, each time as if it were the first time. Each pipeline was a unique snowflake. Each snowflake had unique bugs. Each bug required unique debugging at unique hours.

The revelation: Snowflakes are intricate structures which are ultimately completely random. They do not belong in data engineering.

In our beforetimes, new datasets required a bespoke DAG to:

- Ingest: Figure out where the data lives, how to pull it, how to land it.

- Transform: Build the table, try not to break schemas, remember to add metadata (maybe).

- Validate: Perhaps some tests, if we remembered and had time.

- Publish: Hope the build pattern is consistent across DAGs and doesn’t break dashboards.

But, we realized that every new pipeline we built was secretly four things:

- A way to write the data.

- A way to audit it.

- A way to publish safely.

- And a handful of environment‑specific hacks so dev and production wouldn’t eat each other alive.

You can do that once or twice by hand. Do it a hundred times and you either need to build abstractions or you start leaving little notes in the codebase like a trapped character in a Kurt Vonnegut novel.

We chose abstractions.

The Pattern: Write-Audit-Publish

In our warehouse, every dataset follows the same three-act structure:

I: Write to staging

Never touch production directly. Never. Write to a temporary location where failure is cheap and mistakes are private.

II: Audit the staging data

Test everything. Check everything. Validate that reality matches expectations. If it doesn’t, stop. Use the temporary dataset to dig in and figure out what went wrong, then go fix it. Most of the time it’s better to have stale data than wrong data.

III: Publish atomically

If the tests pass, swap the staging data into production in one atomic operation and document the dataset. Either it works or it doesn’t. No half-measures. No “mostly correct” data.

Simple in theory. The trick is making it impossible to bypass. So, we encoded the pattern into reusable components so thoroughly that building a pipeline any other way feels like punishment.

Enter: Airflow Task Groups and a DAG-factory pattern to automatically generate DAGs from simple file declarations.

The Factory Floor

The core idea: tasks should be declarations, not implementations.

Instead of writing Python code to wire up operators, connections, and dependencies, we write files that declare:

- What data we’re working with and how it should be produced

- What it means (documentation)

- What must be true about it (tests and validations)

- Where it lives (schemas, tables)

- How it should behave (environment-specific config)

Our DAGs are generated from these declarations. We built this using a directory-based convention where each folder becomes a DAG and each file becomes a task, with frontmatter driving the behavior.

What a Declarative Task Looks Like

Building a model, ingesting data from an API, etc. is simply a SQL or Python file with YAML frontmatter that declares metadata and behavior. For example, this builds a dataset for a ledger of daily transactions in our data warehouse:

/*

operator: include.task_groups.transform.CreateTable

description: >-

Cleaned table of credit balances per credit grant, does not include estimated daily consumption. This is the official ledger, transactions against the credit grants only occur when invoices process or manual deductions are created.

fields:

date: >-

Date within credited period (between effective date and expiration date of credit).

metronome_id: Unique identifier of the organization in Metronome.

credit_item_id: ID of credit item, credits can have multiple grants.

granted_amt: Credit amount granted on date.

consumed_amt: Credit amount consumed on date.

expired_amt: Credit amount that expired on date.

voided_amt: Credit amount that was voided on date.

start_amt: Credit balance at the start of day.

end_amt: Credit balance at the end of day.

priority: >-

Order in which the credit is applied if two of the same name exist on a given day.

schema: !switch_value

sandbox: sandbox_schema

default: model_finance

replace_map:

commons: !switch_value

sandbox: dev.commons

default: commons

primary_key:

- credit_item_id

- date

foreign_keys:

credit_item_id: model_finance.credit_grants.credit_item_id

metronome_id: model_finance.metronome_ids.metronome_id

tests:

check_condition:

- description: >-

End amount should be the summation of changes that occurred that day.

sql: >

TO_NUMBER(start_amt + granted_amt - consumed_amt - voided_amt - expired_amt, 20, 2) = end_amt

- description: Check for date gaps in credit balance

sql: >

COUNT(date) OVER (PARTITION BY credit_item_id) = MAX(date) OVER (PARTITION BY credit_item_id)

- MIN(date) OVER (PARTITION BY credit_item_id) + 1

*/

SELECT ... SQL here ...

This frontmatter is the entire specification. It describes:

- Which Task Group to use (

CreateTable) - the orchestration pattern - What the table means (

description,fields) - self-documenting - What must never be broken (

primary_key,foreign_keys,tests,validations) - quality gates - Where it lives (

schemathat’s environment-aware) - deployment config

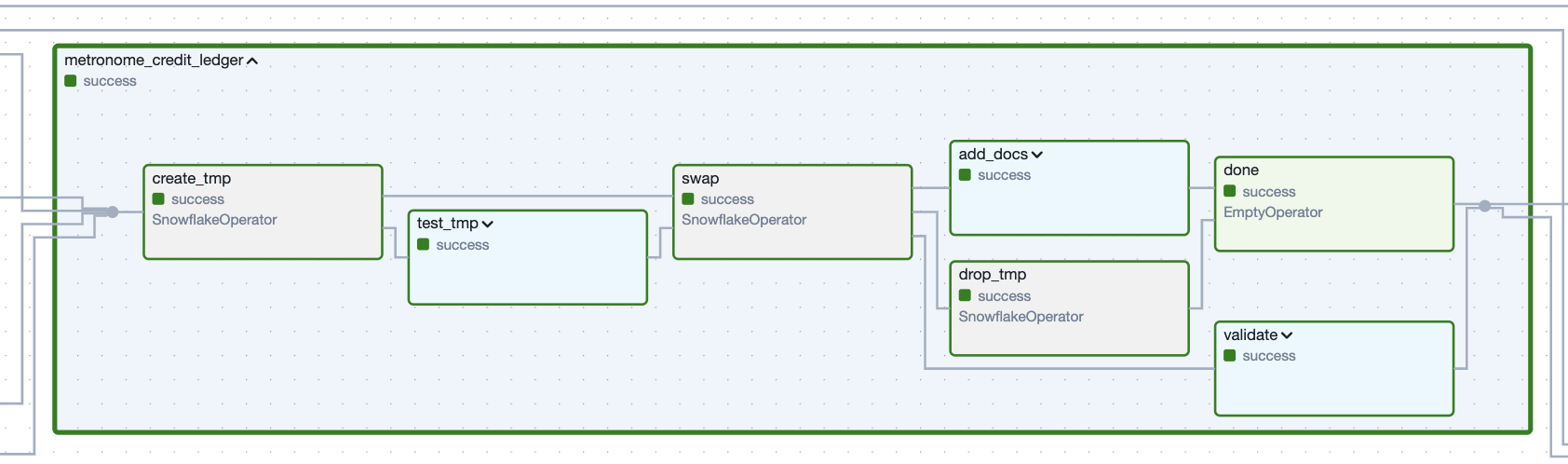

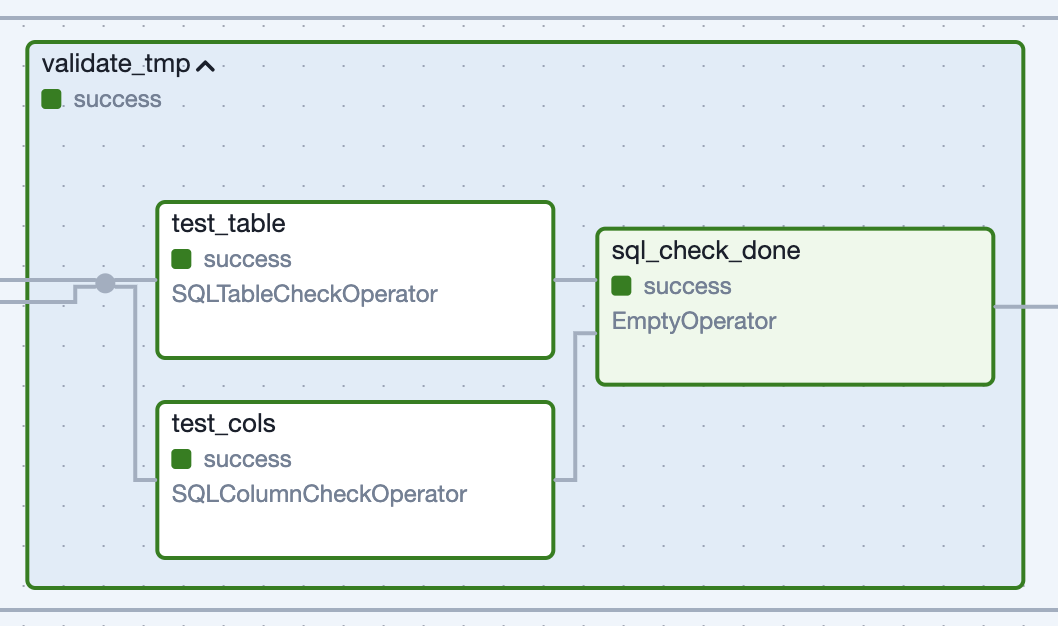

Figure 1. The Task Group which creates the ledger dataset defined by the example code snippet.

Figure 1. The Task Group which creates the ledger dataset defined by the example code snippet.

The SQL below the frontmatter is pure business logic. The framework reads this declaration and generates complete Airflow tasks with batteries included: testing, atomic swaps, documentation, and dependency wiring.

Authors focus on the story of the data in the appropriate language. The Task Groups handle the machinery. They are the bridge between high-level declarations and low-level Airflow orchestration and handle:

- Staging data before it touches production (write)

- Running tests and validations automatically (audit)

- Atomically swapping data into place (publish)

- Generating documentation from metadata (self-documenting)

Let’s walk through the key ones.

The Ingestion Line From DataFrame to Data Warehouse

Let’s write a Python function that fetches data from an API. It returns a pandas DataFrame and we need to load this raw data to a table.

Old way (the artisanal approach):

- 150 lines of boilerplate for

- Figuring out cloud storage bucket structure

- Handling partitioning

- Creating/updating Snowflake stages

- Writing COPY INTO statements

- Adding metadata columns (if you remember at whatever-o’clock you are writing the pipeline)

- Handling the dev/prod environment differences

New way (the factory approach):

# operator: include.task_groups.load.DfToWarehouse

# python_callable: main

# partition_depth: time

# partition_delta: !timedelta 'hours: 1'

# security_group: general

# data_source: splunk

# schema: !switch_value

# sandbox: env__sandbox_schema

# default: in_splunk

# col_types:

# apiVersion: string

# astroClient: string

# astroClientVersion: string

# method: string

# operationId: string

# organizationId: string

# organizationName: string

# path: string

# requestId: string

# status: string

# subjectId: string

# subjectType: string

# timestamp: timestamp_ntz

# userAgent: string

# ---

def main(*data_interval_end: DateTime*, *partition_delta: timedelta*) -> DataFrame:

df = ... some logic to pull from an API idempotently

return df

That’s it. That’s the entire spec.

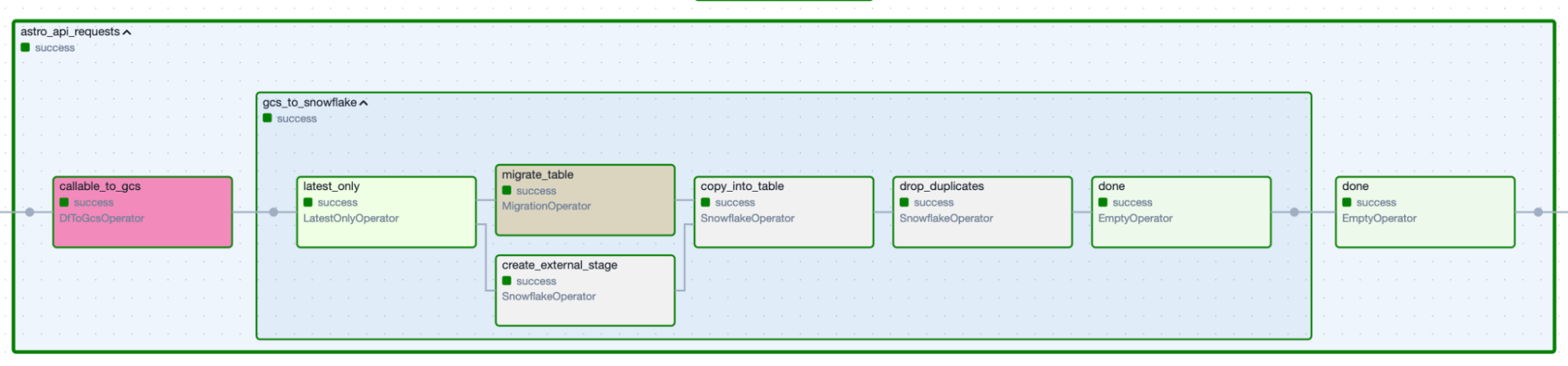

Figure 2. Data-ingestion Task Group produced by the specification above.

Figure 2. Data-ingestion Task Group produced by the specification above.

The Task Group handles everything else:

- Runs the function

- Validates the returned DataFrame matches the declared column types aka data contract (failure here = immediate stop, no bad data proceeds)

- Writes to cloud storage with proper partitioning and naming

- Creates the Snowflake external stage (if needed)

- Executes

COPY INTOwith metadata tracking (which file, when, by whom) - In dev environments: offers to clone from production instead of hitting the real API

- Emits an Airflow Asset so downstream DAGs know fresh data exists

We wrote a function and some YAML. The Task Group did the rest. The pattern is the same whether you’re ingesting from Salesforce, Stripe, or a cursed Google Sheet.

The Transformation Line for Refreshing or Incrementing Data

Refreshing datasets

We need to write SQL that computes a table, classic. Now what?

Old way:

80 lines of DAG boilerplate to

- Construct a

CREATE TABLEstatement - Run SQL

- Add some tests (maybe)

- Add documentation (probably not)

- Wire up dependencies

- Deploy and discover problems in production

New way:

/*

operator: include.task_groups.transform.CreateTable

description: Cleaned Salesforce account table.

schema: model_crm

primary_key:

- acct_id

foreign_keys:

owner_id: model_crm.sf_users.user_id

fields:

acct_id: Account ID.

acct_name: Account name.

total_arr_amt: Total annualized recurring revenue.

validations:

check_condition:

- description: All customers must have a support level

sql: NOT is_current_cust OR support_level IS NOT NULL

*/

SELECT

id AS acct_id,

name AS acct_name,

total_arr AS total_arr_amt,

...

FROM in_salesforce.account

Look at that frontmatter. We’ve simply declared:

- What this table is

- What its primary key is

- What its foreign keys point to

- What each column means

- What business rules cannot be violated

Now watch what happens:

Write Phase:

- The Task Group runs the SQL and creates a temp table from the result

Audit Phase:

- Auto-generates tests for the primary key

- Runs custom validations (the support level check)

- If anything fails: stop the pipeline, production is untouched

Publish Phase:

- Atomically clones the temp table into the production version (zero-downtime swap)

- Drops the temp table

- Applies documentation (table comments, column comments, constraints)

- Emits an Airflow Asset

…all with just SQL and YAML. No DAG code. No operator imports. No dependency wiring. The factory handled it.

Incrementing datasets

Not everything can be recomputed from scratch. Event logs. Transaction histories. Anything with three years of data growing by 10GB per day.

For these, we need incremental logic. And incremental logic is where most teams’ nice patterns go to die.

Not us. We built a Task Group for it.

/*

operator: include.task_groups.transform.IncrementTable

description: Daily transaction ledger.

schema: finance

primary_key:

- transaction_id

col_types:

transaction_id: string

transaction_date: date

amount: float

customer_id: string

...

*/

SELECT

id AS transaction_id,

date AS transaction_date,

amount,

customer_id

FROM source_table

WHERE

{% if not fetch_all_data %}

-- Only grab new data since our last run

date > (SELECT MAX(transaction_date) FROM {{ schema }}.{{ table }})

{% else %}

-- Full reload: grab everything

...

{% endif %}

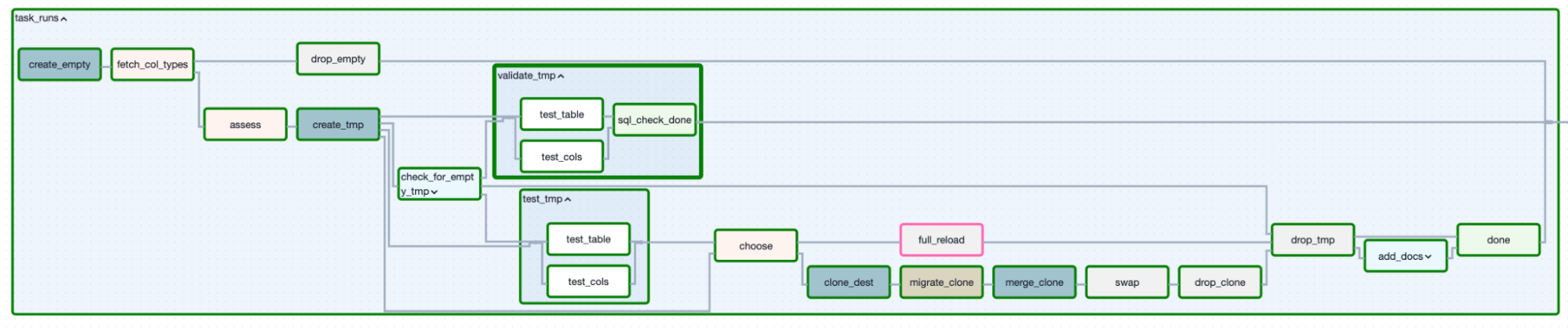

Figure 3. Incremental loading determined a decision-based approach.

Figure 3. Incremental loading determined a decision-based approach.

Notice the {% if fetch_all_data %} logic? That’s a variable the Task Group manages. We write the SQL once with both paths. The Task Group decides which path to take.

The decision tree:

-

Assessment: Does the table exist?

- No → Full reload path

- Yes → Continue

-

Assessment: Do the current columns match what you declared?

- No → Full reload path (schema changed, need to rebuild)

- Yes → Continue

-

Assessment: Did someone manually set

full_reload=truein the DAG config?- Yes → Full reload path

- No → Incremental merge path

Full reload path:

- Fetch all data

- Write to temp table

- Test temp table

- Clone temp table to production

- Drop temp table

Incremental merge path:

- Fetch only new data

- Write to temp table

- Test temp table

- Clone production table to a second temp (the “clone”)

- Migrate the clone’s schema if needed (new columns? Type changes? We handle it)

- Merge (upsert) from temp table into clone based on your primary key

- Test the clone

- Atomically swap the clone into production

- Drop both temp tables

Fin.

All of that decision logic, schema migration logic, merge logic – it lives in one Task Group. When we fix a bug in incremental loading, it’s fixed for every incremental pipeline.

Effectively we wrote SQL with an if-statement and out popped a fully-managed incremental loading system.

The Quality Control Station

Here’s the secret to our testing philosophy: tests must run before publishing, or they’re theater.

If your tests run on your production data, you’re not testing – you’re monitoring. Monitoring is fine. But monitoring doesn’t prevent bad data from reaching the dashboard or that new-fangled AI thing (which actually amplifies poor data quality). It just tells you about it afterward.

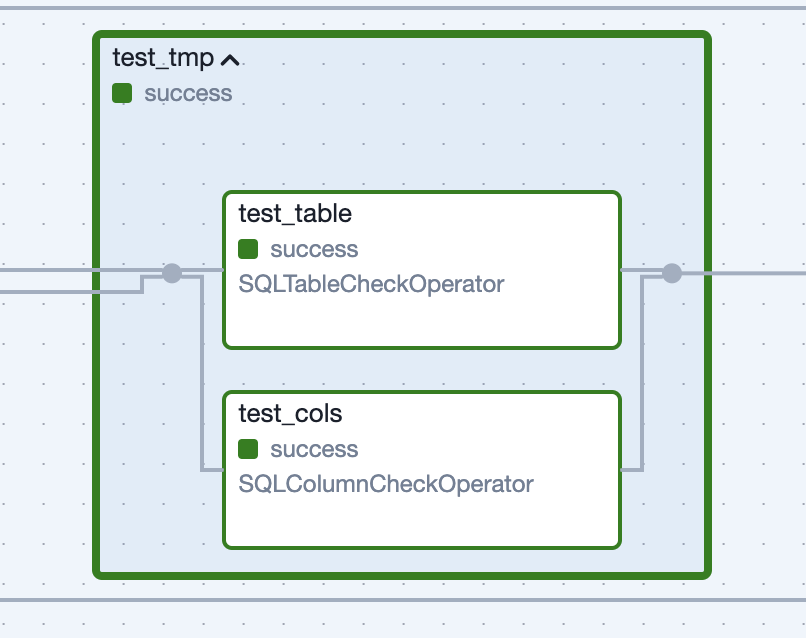

If you read our earlier piece on data quality with Airflow, this is that philosophy baked into a single reusable building block, creatively named TestTable.

The audit step is where the declarative framework’s metadata becomes executable. Tests declared in frontmatter become actual Airflow tasks that block bad data from reaching production. It’s worth noting these tasks are Airflow-native SQL-check operators to inspect tables as a whole and columns. No external tools, just letting Airflow take the wheel.

Our tests run on temp tables. On staging data. On the thing we’re about to publish, not the thing we already published.

Auto-generated tests:

Declare a primary key in the frontmatter? We get:

- Uniqueness test (no duplicate keys allowed)

- Non-null test (no missing keys allowed)

Automatically. We didn’t write them. They exist.

Custom tests:

tests:

check_condition:

- description: Revenue should be non-negative

sql: total_revenue >= 0

- description: End balance equals start plus changes

sql: |

ABS(

(start_balance + deposits - withdrawals - fees)

- end_balance

) < 0.01

These run against the temp table. If they fail, the pipeline stops. Production remains pristine.

Figure 4: Task Group generated for tests run against the unpublished dataset.

Figure 4: Task Group generated for tests run against the unpublished dataset.

Soft validations:

Sometimes we want to warn without failing:

validations:

check_condition:

- description: Revenue did not drop by more than 20% (WARNING ONLY)

sql: total_revenue > (previous_total_revenue * 0.8)

This will log a warning and send an alert, but won’t stop the pipeline. For “this looks weird but might be legitimate” scenarios.

Figure 5: Task Group generated for “soft validations” run against the published dataset.

Figure 5: Task Group generated for “soft validations” run against the published dataset.

The key: all of this is declarative. We write YAML. The Task Group runs the tests. The pattern ensures you can’t accidentally skip testing.

We have tests everywhere. Because we invested in proving our data is reliable, our team and the data is trusted. Trust is the only currency that matters in data engineering. You can have the fastest pipelines, the cleverest SQL, the most elegant architecture, but if nobody trusts your data, you have nothing. You’re just another charlatan with a dashboard. But when your data is tested – boundlessly, automatically, every single time – trust becomes inevitable. Not because you’re good, but because the system won’t let you be bad. And that trust? That trust buys you everything. Room to experiment. Permission to fail. Time to build another new-fangled AI thing. And that trust? Testing is how you earn it.

Maintaining an Inventory

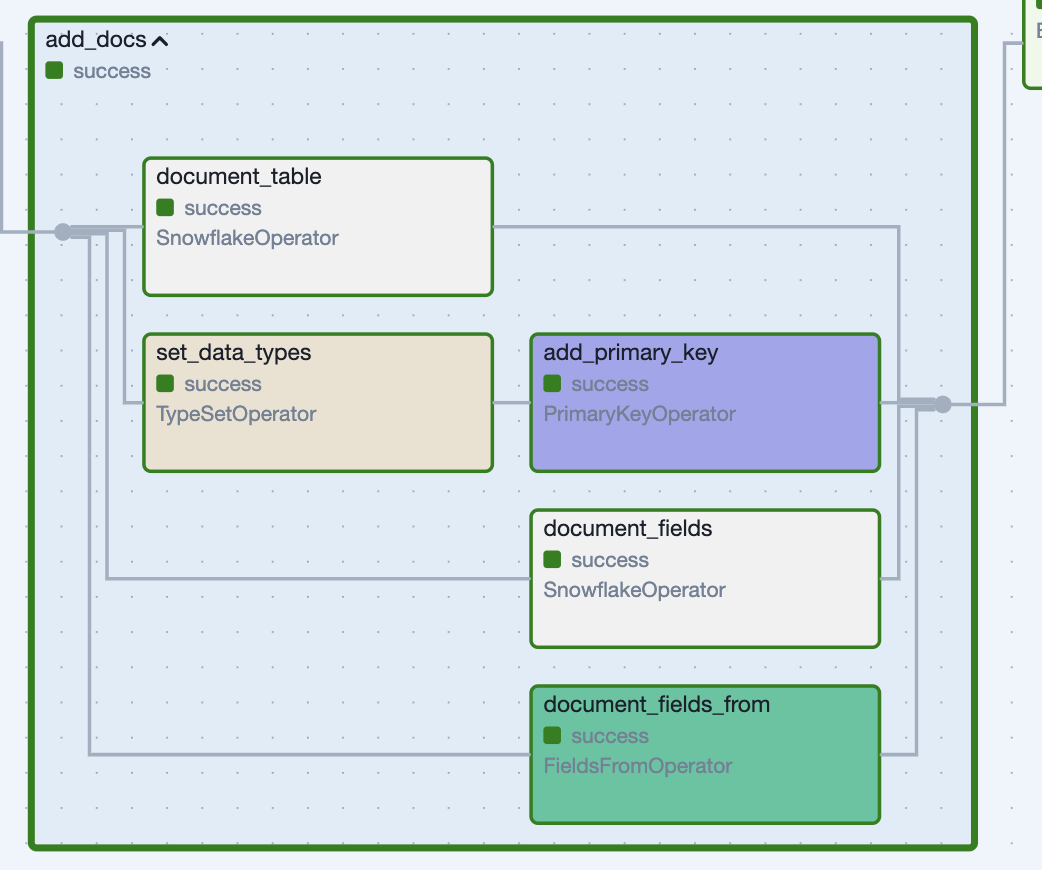

We developed a specific Task Group to document or apply metadata to datasets (table/column comments, PK and FK constraints, etc.) for data discovery – again, creatively named AddDocs. This Task Group can be used anywhere we want said documentation applied (usually called automatically by CreateTable or IncrementTable). We are our own librarians.

*Figure 6: Applying documentation and constraints with a Task Group.*

*Figure 6: Applying documentation and constraints with a Task Group.*

For us, documentation is infrastructure. It’s not a separate chore; it’s part of publishing.

The Foreman of the Factory

All these Task Groups would be useless if you had to manually wire them together every time. That’s where our DAG factory comes in.

We construct a directory structure which allows us to focus on the code and stories we need to write.

dags/

├── 00_ingest/

│ ├── ingest_salesforce/

│ │ ├── METADATA.yml # DAG-level config

│ │ ├── accounts.py # Task: Python file

│ │ ├── opportunities.py # Task: Python file

│ │ └── contacts.py # Task: Python file

├── 02_model/

│ ├── model_crm/

│ │ ├── METADATA.yml

│ │ ├── accounts.sql # Task: SQL file

│ │ ├── opportunities.sql # Task: SQL file

│ │ └── revenue.sql # Task: SQL file

Each folder becomes a DAG. Each file becomes a dataset produced by the Task Group specified in its frontmatter.

The magic: dependency detection.

When the DAG factory reads revenue.sql, it:

- Parses the SQL

- Finds

FROM model_crm.accountsandJOIN model_crm.opportunities - Automatically makes

model_crm.revenuedepend on both upstream tasks (aka tables)

Again, we don’t wire dependencies manually. They’re in the SQL, where they belong. If we reference a table, we depend on it.

The entire DAG creation:

from the_dag_factory import create_dags

create_dags(

dag_dir='path/to/files/in/a/pipeline/',

env=globals(),

**some_shared_defaults

)

One function call. Dozens of DAGs materialize, each following write-audit-publish, each with proper dependencies, each tested, each documented.

Why This Matters to Us

Most systems fail because humans are involved, and humans are chaos engines. We forget things. We take shortcuts. We say “I’ll add tests later” and then never do.

The only way to beat human fallibility is to make the right thing the easy thing. Make it easier to follow the pattern than to break it.

That’s what our architecture does.

Want to add a new dataset? Drop a SQL file in the right folder with a few lines of YAML frontmatter. The tests, the atomic swap, the documentation, the asset emission – all of that happens automatically. Breaking the pattern requires more work than following it.

Write–audit–publish used to be a slogan. Now it’s how our Task Groups actually work, enforced by the declarative framework:

- Write: Land data with rich metadata and sensible staging.

- Audit: Test, validate, and document as part of the pipeline – driven by metadata, not manual steps.

- Publish: Atomically swap into place, emit datasets, and safely push out to the world with added context for other humans to know what’s available.

Most organizations move slow because they’re afraid. Afraid to break things. Afraid to publish without five layers of approval. Afraid to let engineers make decisions. Trust me, we had some reliability issues (but the key word there is had).

If your system is genuinely safe – if you literally cannot publish bad data because the tests run first, if you literally cannot break production because you’re writing to temp tables first, if you literally cannot lose data because every swap is atomic – then you can move fast. You can let a junior engineer add a new pipeline their first week. You can deploy ten times a day. You can try weird experimental stuff like a clone-from-prod pattern in dev environments so you’re not hitting real APIs.

Fear is expensive. Safety is cheap if you build it into the foundation.

Over and over. The same pattern. The same safety. The same boring reliability. It’s not sexy. It’s not revolutionary.

But we sleep at night and it just works. In data engineering, “it just works” is the highest compliment you can give (other than “OMG I totally use that dashboard you created 2 years ago every day”).

What This Bought Us (with receipts)

In the past year, our team of 4 data engineers has:

- Built and maintained over 275 pipelines

- Run 1.6 million tasks every month

- Ingested from 25+ data sources (APIs, databases, CSVs, Google Sheets, Prometheus metrics, you name it)

- Created hundreds of transformed tables covering models, marts, and metrics/aggregations

- Delivered data to Salesforce, internal APIs, internal and customer-facing dashboards and reports

- Kept it all running with minimal firefighting

We’re not heroes. We’re not working 80-hour weeks. We’re just using a factory enabling a small number of repeated patterns. We picked patterns that worked for us. Like doorknobs. You turn it, the door opens. Nobody waxes poetic about doorknobs, but everybody depends on them working every single time.

Here’s what changed:

Before:

- New pipeline = 2-3 days of work (API integration, cloud storage setup, Snowflake loading, testing, documentation, DAG wiring)

- Bugs discovered in production because testing was manual and inconsistent

- Documentation? What documentation?

- Dependencies managed by hand and probably missed ones here and there is our vast data mesh

After:

- New pipeline = a few hours (mostly writing SQL and YAML frontmatter)

- Bugs caught in temp tables before they hit production

- Documentation auto-generated from the same frontmatter that controls the pipeline

- Dependencies auto-detected from SQL and declared relationships

The secret: We wrote the complexity once in the TaskGroups, then reused it everywhere. Now when someone finds a bug in how we handle schema drift, we fix it in IncrementTable and it’s fixed for every incremental pipeline. When we want to add a new test pattern, we add it to TestTable and it becomes available to every pipeline.

This is the factory pattern. This is why Ford didn’t hand-build every Model T.

Because these patterns live in reusable Task Groups and are wired together by our declarative framework, adding a new dataset means adding a single file with frontmatter and business logic (SQL or Python). The orchestration machinery – the paranoia, the safety rails, the metadata tracking, the documentation – is inherited automatically.

We’ve automated just enough of the complexity to focus on the human part: deciding which questions are worth asking of the data in the first place.

Feel free to fire over any questions, concerns, compliments, or complaints on how we do things. If you haven’t noticed, I like to pontificate on these matters. Adios, nerds.

Get started free.

OR

By proceeding you agree to our Privacy Policy, our Website Terms and to receive emails from Astronomer.